CALL FOR ART

Impact: A Members' Exhibition in collaboration with the Fitchburg Art Museum

ArtsWorcester main galleries

Registration Deadline: February 8, 2023

Drop off period: February 16 - February 19, 2023

Exhibition run: February 25 - April 8, 2023

Reception: March 3, 2023, 6-9 PM

Pick up period: April 13 - April 16, 2023

For the eleventh annual Call and Response exhibition, ArtsWorcester and the Fitchburg Art Museum invite artist members to bring one artwork that explores any way humanity and nature impact one another.

The natural world has always inspired artists with its beauty, power, and the raw materials it offers for art-making. Today, in the face of our climate crisis, many artists bear witness to and represent environmental changes in their work–even as others draw from the beautiful ways humans have shaped and utilized the earth.

Artist members are asked to consider humanity’s complex relationship with our environment, along with one (or more) of ten artworks on loan from the Fitchburg Art Museum. These ten artworks explore a range of impacts on the natural world in their themes, subject matter, and materials. View the loan below.

The Fitchburg Art Museum’s curatorial staff will select ten works from Impact by ArtsWorcester artist members to be exhibited at FAM with the loaned works.

We thank our friends and partners at the Fitchburg Art Museum for sharing their collection so generously with our artists.

ArtsWorcester exhibitions are sustained in part by the generous support of the C. Jean and Myles McDonough Charitable Foundation.

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Bulldozed Slash, Tillamook County, Oregon

gelatin silver print photograph, 1980, 7 1/16” x 9 3/16”

Gift of Jude Peterson, 2009.14.2

This image fits into Robert Adams’ ongoing work documenting the depths of damage inflicted on Western America’s wildernesses. Yet, Adams strives to locate more than emblems of man-made destruction—he searches for signs of regrowth and ecological complexity embedded in the remaining forests. In his mind, the higher aim is “to face facts but to find a basis for hope.”

Winslow Homer (American, 1836 - 1910)

Gathering Berries

wood engraving, 1874, 9 ⅛” x 13 ⅝”

Gift of Chris Welles Feder in memory of Irwin Feder, 2018.218.37

“[Winslow Homer’s] prints trace developments in his compositional strategies and preferred subjects—domesticity, leisure, and manual labor, all set against idyllic New England landscapes—that continued even after he abandoned illustration in the late 1880s. The images also cultivated a specific vision of America during an era of immense social, political, and technological transformation. They would have been printed by the thousands and purchased widely by an increasingly literate middle-class population. Homer’s illustrations provide insight into the production and circulation of images that masterfully encapsulated America at this moment.” – Scenes in Circulation: Winslow Homer’s America, Fitchburg Art Museum.

Homer’s widely consumed illustrations of domestic interaction with tranquil landscapes reflect the importance of the natural environment—and its ready susceptibility to human development—to the American popular consciousness.

Laura McPhee (American, b. 1958)

The Blue Lagoon, Svartsengi Geothermal Pumping Station, Iceland

chromogenic print, 1988, 29 ¼” x 37”.

Gift of Dr. Anthony Terrana

“Inspired by the long tradition of landscape photography that imagined nature as a sublime and spiritual place...McPhee decided to capture not only nature’s awe-inspiring beauty, but also the relationship between the environment and technology. The water in Iceland’s most popular bathing destination, the Blue Lagoon, is a byproduct of the environmentally friendly Svartsengi Geothermal Pumping Station, which generates heat and energy from seawater.” – Interpretation from the Princeton University Art Museum.

Lionel Reinford (American, 1942 - 2020)

Winter in New England

acrylic painting, 1977, 31” x 46”

Museum purchase through the Sinon Collection Fund and Gift of Mary Levin Koch, 2017.9

“After receiving some basic instruction in painting techniques and materials, Mr. Reinford quickly developed his own signature style based on his observations of art history, folk art, and nature. He uses bright colors, sinuous lines, and clear crisp compositions to create images of places from his childhood in Honduras, to scenes of local interest, to views of landscapes from his travels across the United States and the world. His paintings are also informed by history, folklore, childhood memories, and his vivid imagination. In Mr. Reinford’s world, the sun shines at high noon in cloudless skies. Every detail is clear, and everything is ordered without being rigid. Mr. Reinford says that he paints in a ‘plain style,’ to ‘show the world as he would like it to be.’” – Mr. Reinford’s World Exhibition text, Fitchburg Art Museum.

A clear, unmarred natural environment in harmony with its human inhabitants is crucial to Reinford’s imaginings of an ideal world.

Evelyn Rydz (American, b.1979)

Gulf Pile

colored pencil and graphite, 2012, 11 ¾” x 16 ¾”

Museum Purchase through the Jamie Poppel Collection Fund, 2013.24

Evelyn Rydz illustrates piles of marine debris in response to the monumental issue of plastic pollution in the world’s oceans. Her vivid, carefully composed drawings contrast the dark reality of man-made objects cluttering and clumping in random masses that threaten sea life. Considering the lasting ecological impact of the objects we discard and forget, Rydz calls her audience to look at these gulf piles and wonder if a piece of it was once theirs.

Harvey Sadow (American, b. 1946)

Fire and Flood/Sacred Sites

ceramic, 1989, 10 ½” x 13”

Gift of Ed and Terry Duffy, 2001.22

Harvey Sadow invokes seemingly opposite natural disasters in this ceramic piece to reference the earth’s sacred cycles of destruction and regrowth. Fire and flood are united by their greater function: they decimate their surroundings while simultaneously paving the way for eventual regeneration through soil revitalization. Nature’s higher power resides in its capacity to harmonize obliteration and creation—yet climate change resulting from human intervention wreaks havoc on this natural balance, skewing the cycle towards devastation. Sadow further implicates the fire/flood dyad in his medium, making a piece with high water content clay and forging it in incredible heat. He further uses red and blue glazing in homage to color pairings traditionally associated with fire and water.

Esther Solondz (American, b. 1964)

Untitled (Rust Portrait)

rust and iron filament on cloth, 2006-07, 15 ½” x 22 ¾”

Gift of Karen Moss

Esther Solondz uses her craft to explore and revel in the transformative processes that natural materials undergo. To create Rust Portrait, Solondz arranged iron filings on cotton, overlayed the cloth with salt, and left the piece exposed outdoors for weeks to develop a rust imprint of a face. This piece reflects Solondz’s abiding interest in natural transmutation (like the chemical change of rusting) as a real-world miracle that the artist can shape by collaborating with the environment.

Unknown Fulani (Fulbe/Peul) artist (Mali)

Yellow amber beads

yellow amber, fiber string, 20th century

L.1.2010.4

Amber offers unique, compelling insight into earth’s history and ecological development. Constituted of fossilized resin from prehistoric trees, amber often encases and preserves the detritus of forests and insects from over 40 million years ago. It’s a repository of life far before us that situates humanity’s relative insignificance in the stretch of geologic time. Amber also inspires the human imagination—in parts of Africa, yellow amber (like the beads on this necklace) is considered to bear some influence over cosmic light/shadow, attracting sunlight and repelling darkness. It further offers protection to its wearer.

Unknown artist (Tongan)

Tapa Cloth (ngatu)

mulberry fiber, pigment, arrowroot binder, early 20th century, 33” x 22.5”

Tapa (or ngatu) is a kind of barkcloth made from paper mulberry trees in the islands of the Pacific Ocean. To create the cloth, artists strip the outer layer of mulberry bark from the inner layer, which is then left to dry in the sun before being soaked and beaten into thin sheets. Often, the women of a whole village work collaboratively to fabricate these sheets prior to their decoration with repeating geometric patterns and nature-based motifs such as fish and plants. Tapa may be worn on formal occasions, but is more frequently used for decoration or given to others as gifts at major life events or ceremonies. In that latter respect, tapa carries significance as a social currency—a Tongan family without any tapa at home or available to donate at important events is considered poor, regardless of their actual financial status. Tapa then represents the transformation of natural materials in the service of social enrichment.

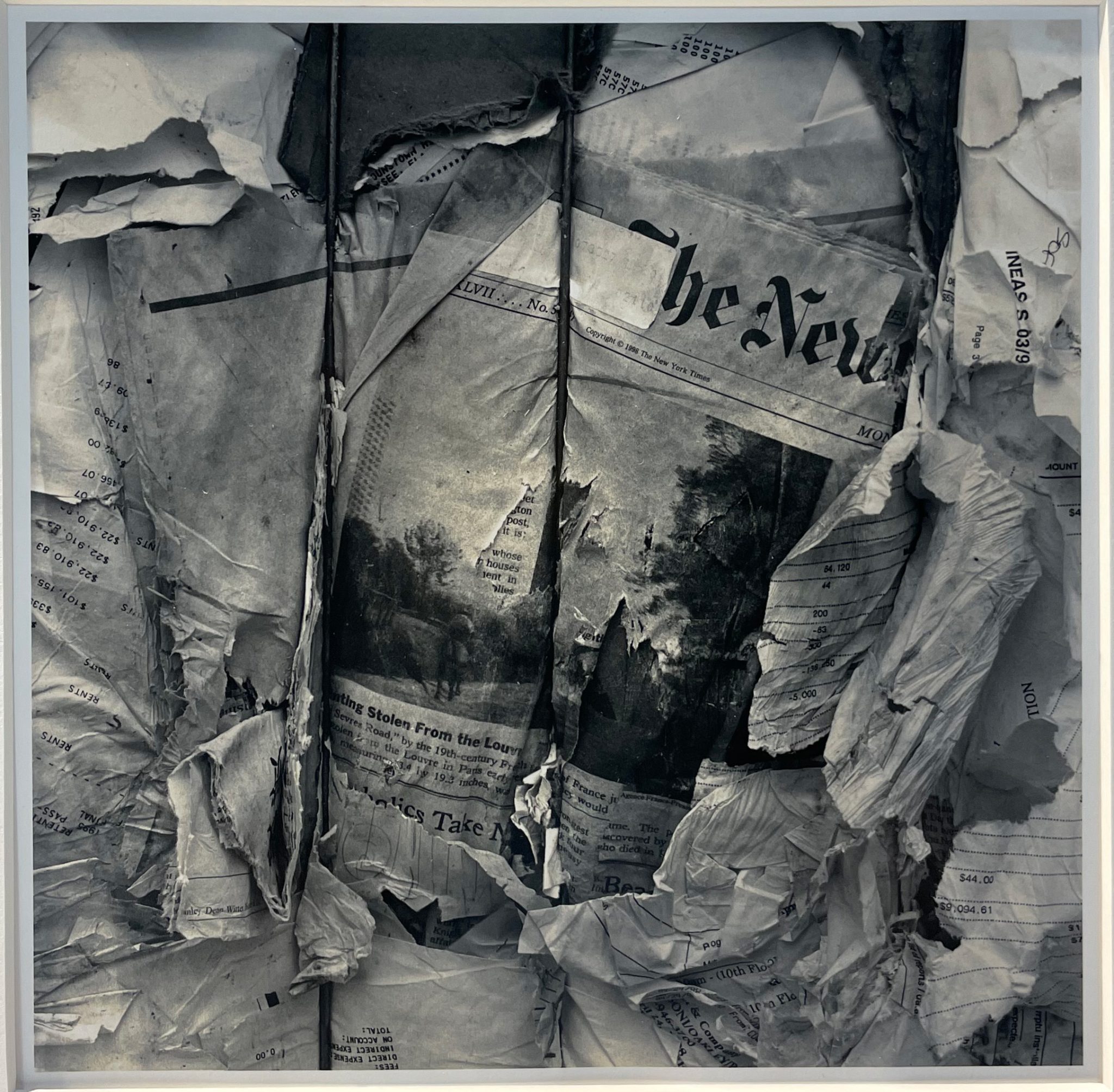

John Willis (American, b. 1976)

Recycled Realities #1

gelatin silver print photograph, 1998, 7” x 7”

Gift of Dr. J. Patrick and Patricia Kennedy, 2017.126

John Willis was inspired to create the Recycled Realities series after viewing a bustling mill surrounded by acres of scrap paper destined for recycling. By arranging and photographing stray scraps from this mill, Willis conducts an archeological dig into society’s offloaded waste while pondering the paradoxical relationship between industrial recycling and pollution. In the artist’s own words: “The more sensitive we are to the volume and degree of waste we create, the more aware we will be in understanding the product of our society...This excess and scrap is at this plant for recycling, which is positive, but also creates some degree of pollution. Who knows where the balance of positive and negative effects from our prolific use of paper products lies?”

All images are courtesy of the Fitchburg Art Museum.